Introduction

The purpose of this series is to inquire, examine, study, and uncover some of the facts, truths, realities, and complexities of change management. The goal is to build a solid understanding and foundation for effectively dealing with change implementation challenges.

Depending on which consulting firm or business school guru you ask, 50% – 80% of ALL change programs fail. These experts all have different definitions of “change programs” and “change failures”. We encounter and address change constantly every day. When does it become a “program?” And, when does it become a “failure?”

It doesn’t really matter so much about the definitions and the percentages. The point is that managing change is a critical issue that isn’t being effectively handled. As we ponder some components of managing change, it will become clearer why there is a problem. And, through these considerations, we’ll see some things that can be done to improve change implementations on a day-to-day basis.

Background

My first job after graduating in 1963 with a degree in physics, was a member of the Guidance and Control team for the Apollo Program. The approaches they worked out for problem definition, analysis, solution, and implementation, provided an exceptional learning experience for managing change.

Flying to the moon – vehicle designs, rocket engines, space suits, space navigation, flying techniques, landing techniques, return protocols – stuff never done before. Talk about change! The approach used by NASA in creating and implementing the complex changes from conventional aviation required for space travel, provided the guidelines for many of my successes including 8 years as the COO and change czar for a Fortune 500 company. Through many change programs, I have had interactions with many of the great business gurus and self-proclaimed experts – most of whom have never been accountable for any change programs, large or small. They were smart people and had great ideas including useful techniques. But, very, very few could make it happen. Their approaches to implementation typically fell short. Just look at the reengineering outcomes of the 80’s and 90’s. It continues to be unimpressive, even today. In this series, we will be looking at why. (Never discount the gurus. They are smart and have great ideas. Just don’t blindly embrace their “wisdom.” Instead, filter it through the considerations we suggest here.)

One important thought to ponder as a benefit of the Apollo Program experience is this: the method of approach to change far outstrips experience in managing change. After all, no one had any experience in going to the moon, but we did it with how we approached the problems – how we changed our approach to flying to meet the new needs of space travel. Applying previous change management experience to a new challenge without an appropriate method is doomed. That is what a lot of consulting firms do – and fail in the process. But they do put on a good, expensive show.

For this series, we reflect on some of our experiences. We will be referring to ABC Company – the names have been changed to protect the guilty and the victims.

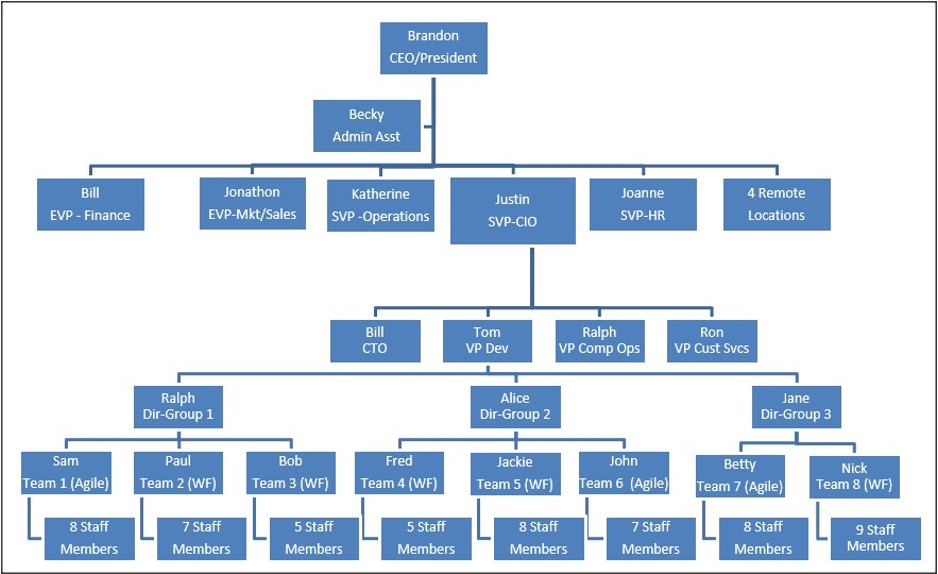

Examples in this series are not taken from one particular company, but multiple ones. The organizational structure above is used to put the situations in perspective and identify the responsibility levels of those involved. The scenarios described are real.

Undoubtedly, you will believe that you are currently doing many of the considerations we address in this short series – at various levels of effectiveness. Most people are not aware of them in the sense that they deliberately focus on them. These considerations are not on their front burner. We challenge you to put them on your front burner and improve them until they become a part of the way you perform. Manage change every day. Don’t let it manage you.

We Invite Your Collaboration

We invite your collaboration in this series as we consider some of the challenges inherent in changing what is done and how it is done. We also challenge you to introspect, to honestly consider your own state and feelings, such as:

- How good is your situational awareness?

- How much do you depend on what your direct reports tell you?

- How much do you depend on what your immediate supervisor tells you?

- Do you verify what you are told? What do you do?

- How comfortable are you with your awareness of what is going on?

- Do you believe managing change is any different from day-to-day management? If so, Why? What do you have to do differently when managing change?

- How well do you work with people you don’t like?

- Do you take your job more seriously than you take yourself? What about your coworkers, do they? What about your direct supervisors and other managers?

- How successful are you in deflecting political gambits into productive behaviors? How do you do it?

- How much of your time is wasted due to your “buttons” being pushed causing you emotional distress, forcing you to make inane decisions?

- Are you worried about controlling people and situations for which you are responsible?

- How strong is your curiosity? Have you succumbed to complacency? Why?

Part 1

Change Management – What Is It?

Change Management – it’s getting people to change what they do and how they do it.

Seems pretty simple. It’s a day-to-day activity, not something that comes along once in a while. Every time we are asked to do something or ask someone else to do something, there is some element of change required. Sometimes that change is small and sometimes it’s extraordinarily large. Managing change is everyone’s responsibility, every day. Let’s look at how easy it is (and isn’t).

Fred is one of three project managers in the ABC company IT department reporting to Alice, Director of one of three development groups. Alice reports to Tom who is the VP of Development. Tom, in turn, reports to Justin the CIO.

Fred’s project is a system development effort (waterfall software development approach) supporting the Marketing Department in their launching of several new product lines. The most knowledgeable person on the project details is Joan. She has been working with a Marketing Department manager (Renee) who has been reassigned. Renee’s replacement, Jack, has requested Fred send over whoever has been working with Renee to bring him up to speed on the project. Fred sends Joan, who is very enthused and has prepared a detailed presentation on the various aspects of the project.

When Joan returns, she goes straight to Fred announcing that Jack is a real jerk. Fred has seldom seen Joan so upset. Then, the phone rings and it’s Fred’s boss, Alice, asking what on earth is going on with the Marketing project. Alice says she understands from the Marketing Department that there are serious problems with the project.

That went well! See how easy change management is? This example is just a small change, a change of one person on the collaboration team. What Joan was doing and how she was doing it with Renee was working fine. Now, with Jack, it isn’t. We have a change management challenge. What are we going to do differently and how are we going to do it?

[Side thought: Suppose instead of involving 2 people, this situation was what we call a major change directly involving 20, 50, 100, or 1000 people. Something like converting a Waterfall development project to an Agile approach. Or merging organizations together. Or putting a complex new system into production. Wow! ]

Joan’s emotional report on the meeting painted Jack as just to the left of Atilla the Hun. Joan felt Jack didn’t listen, made accusations about the competence of the people working on the project, accused Joan of not understanding the overall goals of the project, expressed concerns over meeting schedules, and continuously interrupted her presentation with non-relevant questions.

[Let’s introduce two concepts of visibility here – “on the surface” and “under the surface.” On the surface represents what we observe and constitutes our immediate ‘perception’ of a situation. Under the surface represents what we don’t observe directly but surmise from what we are hearing and seeing on the surface – and what people tell us. These conjectures dangerously add to and skew our ‘perceptions’ of a situation.]

On the surface it certainly looks like Jack is a jerk. That’s certainly Joan’s perception. But under the surface, Fred wonders what the situation really is. And, this simple situation involves all of the considerations for managing change that we want to address in this series, hopefully with your participation and thoughts. This series will address:

- Change Management – What Is It?

- The Nature of People – How Does It Affect What We Do?

- Perceptions – The Unreal Truths

- Culture – This Is How We Do Things

- Behavior Styles – Why Is The Other Person Such A Jerk?

- Behavior Flexing – The Platinum Rule

- Learning Styles – Potential Show Stoppers

- Critical Thinking – Asking Why?

- Epilogue – Putting It All Together

A thought to ponder at this point:

Managing change is a key part of day-to-day management.

This begs a question – if we are managing change as part of our day-to-day accountabilities (such as the Joan/Jack fracas), why do we need to create and emphasize a special “Change Management Project” when introducing new procedures and protocols? Shouldn’t it be business as usual – part of the normal management process?

What might be missing in the Joan/Jack day-to-day approach to what they do and how they do it that contributed to the fracas of their first meeting? Let’s look at some of the considerations that come into play.

First of all, Joan’s “perception” of what went on with Jack is just that – her perceptions. Jacks are different. Joan and Jack are viewing the situation with their own set of filters. We take a look at this consideration in Part 3 Perceptions.

These different perceptions define and validate the rules of engagement for both Joan and Jack. But, since the perceptions are different, so are the rules. We look at this consideration in Part 4 Culture.

The tension experienced in the meeting of Joan and Jack is because they have different behavior styles. Each has different expectations developed from interactions with others, in this case radically different expectations. When expectations are not met, tensions arise. We look at this consideration in Part 5 Behavior Styles.

Joan’s Behavior Style is Amiable meaning she is slow paced (low assertiveness) and relationship oriented (high responsiveness). Jack’s style is Driver meaning he is fast paced (high assertiveness) and task oriented (low responsiveness). Jack’s predecessor, Renee, had a behavior style the same as Joan’s, Amiable. There was very little tension due to the similar behavior style between Joan and Renee. With Joan and Jack, there was maximum tension. Simply put, Joan is a detail and people-oriented person. Jack is a summary (bottom line) and task-oriented person. When they get together, it can be somewhat entertaining if you are only an observer of the behavior style tensions in play.

Behavior style tensions activate physical changes in individuals. This phenomenon we look at in Part 2, the Nature of People. This feature of our physiology is to ensure survival when confronted with the unexpected by releasing adrenaline to enable flight or fight. Other chemicals are released that generate emotional responses to situations. In other words, “buttons are pushed” that lead to emotional responses such as anger, fear, depression, and joy. Authentic communications cease (yes, even with positive feelings). Emotional considerations then rule the day. Treating people the way we would like to be treated sounds good, but only makes it worse because they are not like us. We look at dealing with this consideration in Part 6, Behavior Flexing.

Neither Joan nor Jack has yet learned the practice of Behavior Flexing – stressing one’s self to accommodate the style of the other to increase the odds for authentic communications. The “button pushing” could be reduced if Joan could flex her behavior by picking up the pace of her presentation, not going into detail unless asked, being clearer about goals, and saying what she really thinks – the facts, just the facts at a high level. Jack could also help out by slowing the pace, listening more (and better), not coming on too strong, being more supportive, and trying to make genuine personal contact (appealing to Joan’s people orientation).

Collaborating with others is always a learning experience. Joan was trying to learn from Jack and Jack from Joan. Joan’s Learning Style is Accommodator. She learns best by doing and relating to others. Jack’s style is Assimilator. He learns best by observing and thinking. Another clash to add to the stress factory. Speaking to these learning preferences enhances communications. We look at this consideration in Part 7, Learning Styles.

Failures in effective communications usually occur because the participants continue to be governed by the emotions generated by different behavior styles. One of the most effective ways to break out of this situation is Critical Thinking, which we look at in Part 8. This consideration involves:

- The process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and evaluating information to reach an answer or conclusion.

- Disciplined thinking that is clear, rational, open-minded, and informed by evidence.

- Reasonable, reflective thinking focused on deciding what to believe or do.

- Asking – Why?

- Purposeful, self-regulatory judgment which results in interpretation, analysis, evaluation, and inference, as well as explanation of the evidential, conceptual, methodological, criteriological, or contextual considerations upon which that judgment is based.

And why is this important? Because we want to avoid the perils of trusting our lives and fortunes to the decision-making of people who are gullible, uninformed, and unreflective.

Embracing these considerations as a management practice have greased the skids for a number of complex change programs without the need for a special change management line in the project plan. Big change becomes business as usual.

Whether you decide to embrace ADKAR, Kotter’s 8-Step Model, McKinsey 7-S Model, ODR Model, Hammer Model, or whatever model – making it happen and making it stick requires more. In Part 9, Epilogue, we look at techniques for making these interactive considerations work – for “putting the rubber on the road.”

We continue with a more in-depth look at each of the considerations for managing change. We start with Part 2, The Nature of People.

[…] See Part 1 – Change Management – What Is It? […]