Part 6 in our Change Management Consideration Series

See Part 1 – Change Management – What Is It?

See Part 2 – The Nature of People – How Does It Affect What We Do?

See Part 3 – Perceptions – The Unreal Truths

See Part 4 – Culture – This Is How We Do Things

See Part 5 – Behavior Styles – Why Is The Other Person Such A Jerk?

Psychologists, through extensive research, have shown that 75% of the population is significantly different from each other. In other words, three out of four people important to our success and happiness differ from us in how they think, decide, use time, handle emotions, manage stress, communicate, and deal with conflict.

Our Self-2 (discussed in Part 2 – The Nature of People) expects our environment to remain stable or it will start up the chemical factory (mostly adrenaline) to give us an improved ability for “fight or flight” actions. Anyone with a different behavior style than ours triggers Self-2. So, treating others as we want to be treated (Golden Rule) is going to lead to stress most of the time.

The key to effective relationships and successful communications, from the Behavior Style point of view, is to eliminate the Golden Rule: Do unto others as you would have them do unto you” and embrace the Platinum Rule: “Do unto others as they would have you do unto them.”

If we are going to treat others as they want to be treated, we are going to have to modify our behavior style, momentarily. This means we should learn to “flex” our Behavior Style if we want to be more effective in dealing with others.

Awareness of Behavior Styles provides a means for treating people the way they would like to be treated. The work is done by you, not the other person. You are required to change your style, temporarily, to meet the needs of the other person. This Behavioral Flexibility process is called “Flexing.”

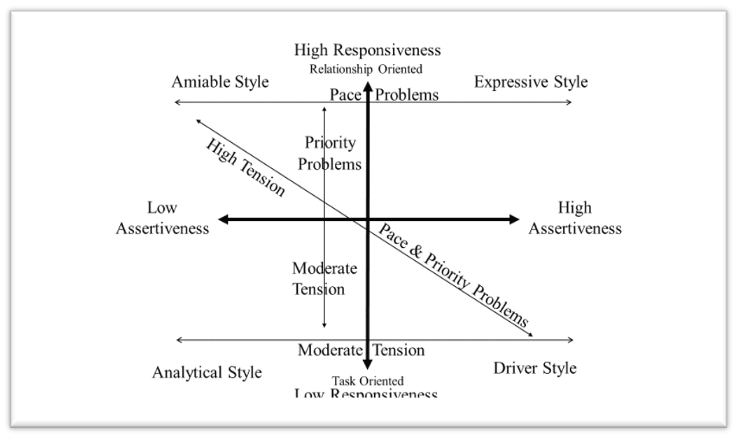

In Part 5 – Behavior Styles, we discussed the tensions that exist between different styles. To illustrate this interaction, we now look (see Figure 1) at a max tension situation where an Amiable and a Driver interact.

Driver vs. Amiable

As an example of behavior flexing, if you are a Driver and want to communicate effectively with an Amiable here are some considerations:

You differ from Amiables on both of the basic dimensions of style. The Amiable is less assertive and more responsive than you are. So, you are likely to experience more style-based differences with Amiables than with either Analyticals or Expressives, both of whom have one basic dimension of behavior in common with you. As a result, there are more types of behavior that you can modify when flexing to an Amiable than when flexing to any other style.

As you read the types of temporary adjustments of behavior that can help you get in sync with Amiables, select carefully the one to four types you think will help you work best with a particular Amiable. It’s not easy to change habitual behavior, even for a short time, so be sure to select only one to four types of behavior to work on. Within each type of category of behavior, a number of specifics are mentioned. Do several, but not necessarily all, of the specifics within the behavioral category you plan to emphasize. You’ll probably think of additional ways to work better with the specific Amiable you have in mind.

1. Make Genuine Personal Contact

The Amiable wants to be treated as a human being and not as a function or a role only. The Driver, who is more task oriented than most people, may need to remember to show a sincere interest in the Amiable as a person.

- Don’t seem aloof.

- At the outset, touch base personally.

- Disclose something about yourself.

- Make the most of opportunities for conversations that are not task related.

2. Slow Your Pace

Amiables walk slowly, talk slowly, decide slowly. To fast-paced Drivers, it seems they do everything at a snail’s pace. But to the Amiable, the fast pace of a typical Driver is very uncomfortable. It throws Amiables off their stride. If you want to work better with Amiables, slow down and get more in sync with their natural rhythm.

- Talk slower.

- Don’t create unnecessarily tight deadlines.

- When it comes to making decisions, don’t rush the Amiable unnecessarily.

3. Listen More, Listen Better

Drivers tend to speak their minds. Amiables are apt to keep their opinions to themselves. If the Driver is also a poor listener, which is often the case, the Amiable is apt to clam up even more. It’s hard to have a productive work relationship when one person isn’t talking. Drivers don’t get the information they need and the Amiable’s active participation begins to dry up. A growing rift settles into the relationship. Though the conversational lopsidedness is certainly not all your fault, it is in your best interest to improve the situation by listening more and better.

- Talk less.

- Provide more and longer pauses to make it easier for the Amiable to get into the conversation.

- Invite Amiables to speak.

- Reflect back to the speaker the gist of what you hear.

- Don’t interrupt.

- Don’t finish Amiable’s sentences.

4. Don’t Come On Too Strong

Amiables, by definition, are less assertive than you. Their body language isn’t forceful. The don’t speak as often and when they do, they’re not as emphatic. So, when you use your normal Driver behavior, the mismatch in assertiveness may lead the Amiable to think of you as pushy. A relationship certainly isn’t enhanced when one person feels he is being pushed around by another. Also, if your way of communicating makes you seem dogmatic, the Amiable may become more silent than usual, thus depriving you of important information. Here are some things you can do to avoid coming on too strong to Amiables.

- Decrease the intensity of your eye contact.

- Don’t gesture too emphatically.

- Decrease your vocal intensity.

- Lean back when you make a point.

- Phrase your ideas more provisionally.

- Be more negotiable.

5. Focus More On Feelings

Amiables are expressive of their emotions and sensitive to the feelings of others. You can get more in sync with Amiables by focusing more on feelings – both theirs and your own.

- Look at the person you are conversing with so you can take in body language cues.

- Concentrate on the meaning of the person’s body language.

- Note how the other person reacts.

6. Be Supportive

Amiables are supportive and they expect others to be supportive in turn. They feel that’s the least thing one human being should be able to expect from another.

- Listen empathically so the Amiable feels heard and understood.

- Express sincere appreciation for the Amiable’s contributions.

- Lend a helping hand.

7. Provide Structure

Amiables tend to be most comfortable and work best in stable, clearly structured situations. Do what you can to contribute to that stability and structure without being overly constraining.

- Make sure the Amiable’s job is well defined and goals are clearly established.

- Help the Amiable plan difficult projects and design complex work processes.

- Reduce uncertainty.

- Demonstrate loyalty.

8. Demonstrate Interest In The Human Side

Amiables tend to take a people-oriented approach whereas Drivers are prone to be task-oriented. When working with an Amiable, give increased attention to the human side of things.

- Invite Amiables’ input on matters that affect them.

- Show that other people support the idea you are advancing.

- Discuss the effects of decisions on people and their morale.

- Provide an opportunity for the Amiable to talk with others before committing to a decision.

Amiable vs. Driver

If you are an Amiable, you differ from Drivers on both of the basic dimensions of style. Thus, you experience more style-based differences with Drivers than with either Analyticals or Expressives, each of which has one basic dimension of behavior in common with you. As a result, you will find more types of behavior you can modify when flexing to a Driver than when flexing to any other style.

As you read the types of temporary adjustments of behavior that help you get in sync with Drivers, select carefully the one to four types you think will help you work best with a particular person. It’s not easy to change habitual behavior, even for a short time, so be sure to select only one to four types of behavior to work on. Within each type or category of behavior, a number of specifics are mentioned. Do several, but not necessarily all, of the specifics within the behavioral category you plan to emphasize. You’ll probably think of additional ways to work better with the specific person you have in mind.

1. Pick Up The Pace

Drivers tend to do everything at a fast pace. You often relate better to Drivers when you increase your pace considerably.

- Move more quickly than usual.

- Speak more rapidly than is normal for you.

- Use time efficiently.

- Address problems quickly.

- Be prepared to decide quickly.

- Implement decisions as soon as possible.

- Complete projects on schedule.

- Respond promptly to messages and requests, in person or by telephone.

- When writing, keep it short.

2. Demonstrate Higher Energy

Drivers are typically high-energy people. When relating to Drivers, there are times when you’ll need to put more vigor into what you say and do.

- Maintain an erect posture.

- Use gestures to show your involvement in the conversation.

- Increase the frequency and intensity of your eye contact.

- Increase your vocal intensity.

- Move and speak more quickly.

3. Be More Task-Oriented

The Driver is usually more task-oriented, and the Amiable tends to be more people-oriented. When working with a Driver, you may want to give increased attention to the task side of things.

- Be on time.

- Get right to business.

- Be a bit more formal.

- Maintain a somewhat reserved demeanor.

4. De-Emphasize Feelings

Drivers are less emotionally aware and less disclosing of their feelings than most people. You can get more in sync with Drivers by being less emotionally disclosing. Be more reserved without becoming cold or aloof.

- Limit your facial expressiveness.

- Limit your gestures.

- Avoid touch.

- Talk about what you think rather than about what you feel.

- Don’t upset yourself if the Driver seems impersonal.

5. Be Clear About Your Goals and Plans

Drivers are the most goal-oriented of the styles. They also take a more planned approach to their work than most people. The Amiable is more apt to take a fairly casual approach to goal setting and planning. This can become a point of tension between the two styles.

- Engage in goal setting.

- Set stretch goals.

- Plan your work.

6. Say What You Think

Drivers tend to speak up and express themselves candidly and directly. Amiables are more likely to keep their thoughts to themselves and speak somewhat tentatively and indirectly. Here’s how you can bridge that behavioral gap.

- Speak up more often.

- Tell more; ask less.

- Make statements that are definite rather than tentative.

- Eliminate gestures that suggest you lack confidence in the point you are making.

- Voice your disagreements.

- Don’t gloss over problems.

7. Cut To The Chase

Amiables are interested in some kinds of information that Drivers could care less about. These very-time-conscious people may get very stressed if you talk about things they don’t think they need to know.

- Concentrate on high priority issues.

- Present the main points and skip all but the most essential details.

- If in doubt, leave it out.

8. Be Well Organized In Your Communication

Drivers expect you to be well organized, brief, practical, and factual. As an Amiable, by contrast, you tend to be more casual and informal when you talk. So, when presenting ideas or recommendations to Drivers, you make your case better when you incorporate the following behaviors.

- Be prepared.

- Have a well-organized presentation.

- When making recommendations, offer two options for the Driver to choose between.

- Focus on results of the action being discussed.

- Emphasize that you are recommending pragmatic ways of doing things.

- Provide accurate factual evidence.

We’ve shown considerable detail for the Amiable/Driver interaction to illustrate possible considerations in Flexing. It is not always necessary to make a major project out of it. Usually, it’s just a matter of watching and listening – making adjustment on the fly. During an interaction, it is not unusual for one player to change their style requiring a different flex from the other party.

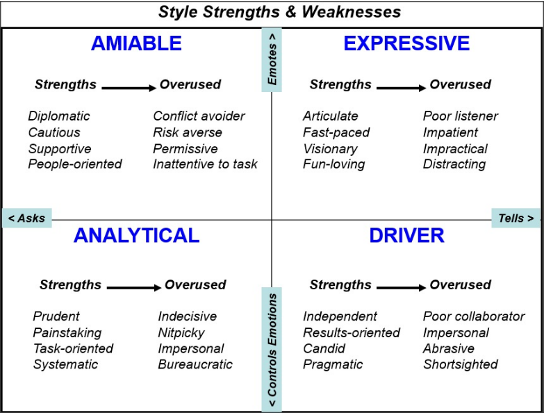

Style Strengths and weaknesses are shown in this chart (See Figure 2) – things you can observe before and during your interaction with someone. The weaknesses come out when the individual “over uses” their strengths.

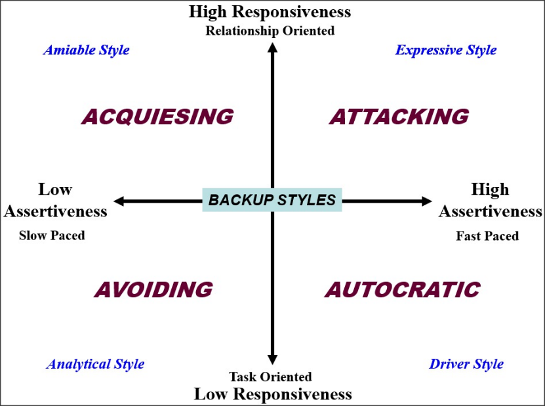

This chart (See figure 3) shows what to expect when the stress during an interaction reaches levels that trigger Self-2 and the chemical factory into overtime.

Being aware of behavior styles and flexing behavior is constantly going on. Many times, we flex automatically and are unaware we are doing it. Being aware can reduce our stress. Next meeting you are in with a group, you may find it interesting to observe the interactions and behavior styles in action. You’ll see lots of situations where a small flex on the part of one person would have gone a long way to effective communications.

Example Situation

As an example of Flexing Behaviors, we consider a situation involving:

Jane: Sr Consultant – Predominant Style: Expressive

Fred: Client – Predominant Style: Analytical

Jane had a lot riding on the review/proposal meeting with Fred, her client. If any items didn’t meet Fred’s expectations, the very large follow-on engagement for the next 3 years would not happen. Fred was the client decision maker on their current and follow-on engagement.

Cost containment was a major client priority now and going forward. It was not a good time to ask for increases and commitments to new endeavors. The key was to show how well the requirements had been collected over the last year and how they contributed to efficient and relatively risk-free project execution. Project management and the ability to galvanize the client/consultant team were even more important for the follow-on commitment.

No one had ever suggested that Jane’s working relationship with Fred was smooth. Once, after a particularly tense encounter, Jane had told her husband, “The interpersonal chemistry definitely is not good.” Through interpersonal communications skills development provided by her firm, Jane had learned a more useful way of describing the problem: She saw that she and Fred were experiencing a clash of styles. Jane is an Expressive, and Fred is an Analytical. Neither is very flexible, and their rigid ways of interacting severely hamper their relationship.

For the past year, Jane’s reports to Fred had not gone well. The more enthusiastically Jane waxed about their accomplishments and plans for moving forward, the more disinterested Fred became. Jane’s colorful visuals received good reviews from some people (especially her boss), but they didn’t impress Fred one bit. Fred’s disdain was evident in his comment that he could be “persuaded by facts,” but could not be “swayed by flash.”

Two points that were stressed in Jane’s training sessions caused her to take a different approach to the upcoming meeting. One was that how a proposal is presented can be as crucial to it getting a good hearing as to what the proposal contains. The other idea that intrigued her was this: “When a relationship isn’t going well, don’t do more of the same; try something different.”

What Jane decided to do differently was to use her newly acquired style flex skills in the crucial meeting. Jane had learned that when five of her colleagues filled out the People Style Assessment on her, she profiled as an Expressive. Using her new Client Style Assessment and her observations, it was obvious to Jane that Fred was an Analytical. Therefore, Jane asked Jim, one of her associates and an Analytical like Fred, to help her plan a more effective approach to the upcoming meeting. They settled on three things that Jane could do differently in order to have a meeting that would be congruent with Fred’s mode of operation.

First, Jane would “open in parallel” – flex to her client’s style from the very beginning of the meeting. Instead of her usual way of trying to build rapport by telling a story or two, she would demonstrate more of a task orientation. Jane planned to keep introductory comments brief and move directly to the purpose of the meeting. It would be a serious, low-key beginning.

Next, Jane’s presentation would be logical and thorough. It would be supported by a written summary and backed by a couple of detailed appendixes. Frank would have all the data he could possibly want.

Jane also decided to rein herself in a bit. She planned to talk less and listen more. Instead of immediately rebutting Frank’s concerns as she usually did, Jane would encourage him to explain his reservations more fully. Once she understood Frank’s point of view, she would acknowledge points of agreement and rely on facts and logic when discussing their differences.

Jane liked the plan but was concerned about implementing it. Though she was only making three changes in the way she would interact, two of the changes were fairly encompassing, and they weren’t behaviors that came easily for her. So, Jane and Jim role-played the meeting. Jim took the part of Frank. The first practice didn’t go well, so they discussed improvements and tried again. This time they were satisfied. Jane told Jim, “I’m as ready as I’ll ever be.”

Jane thought she did quite well at flexing her style in the meeting with Frank. She was aware of occasional lapses, but, by and large, she successfully implemented the plan and was pleased with the outcome. Rapport was the best it had ever been in their meetings. Frank didn’t even make cuts in the follow-on suggestions. Jane concluded that the behavioral changes she made to get on Frank’s wavelength would come in handy in future meetings.

Style flexing worked for Jane. This is not to say that by flexing your style you will inevitably achieve your goals. That is neither possible nor desirable. If by using a certain method, you could automatically get other people to do your bidding, their freedom as human beings would be destroyed and the quality of decisions would plummet. When we say that style flexing works, we mean that there is a high likelihood that rapport will be better and that, as a result, the two will achieve a better outcome.

The point is to establish “authentic communications” by flexing behavior. And, there is another style that plays a big role in managing change – Learning Styles.